Key points

- More than 50% of UK adults do not have a will.

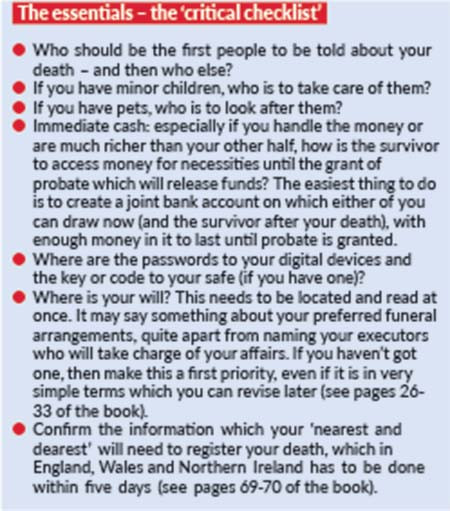

- Take time to list important information and instructions.

- Tax planning can work in conjunction with advance asset planning.

- Involve family in decisions.

Sudden bereavement

‘Enjoy yourself; it’s later than you think.’

(Horace, Roman lyric poet, BC 65-8)

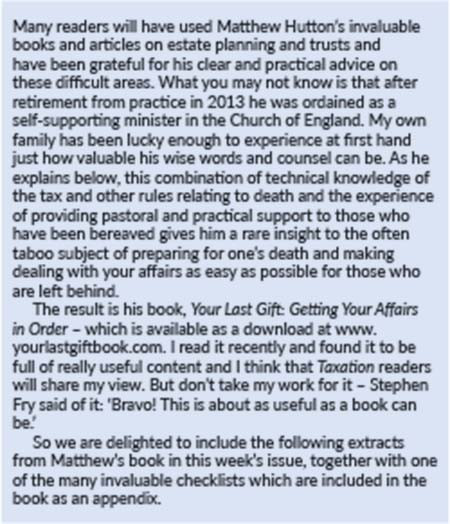

In October 2019, my wife Annie and I were spending a long weekend with friends, two of whom had been widowed fairly recently. One commented that, apart from the devastating grief of sudden bereavement, she had found herself wishing that her husband had left clear information and instructions on management of the family home and financial affairs. The other (who had had time with her husband to get a reasonable feel of what she needed to know) suggested that leaving as full a record as possible of such things might fairly be regarded as a gift to those left behind: hence, the title of this book. A number of the married couples present, and others since, also thought that some essentially practical guidance would be very helpful.

The circumstances in which our friends found themselves are not a matter of gender, age, property values or intelligence. Regardless of ‘who goes first’, far too many couples and indeed individuals have as yet not ‘put their affairs in order’.

That got me thinking. As a former private client solicitor, tax adviser, author and lecturer and, more recently, as a vicar in the Church of England, I have long found myself giving pastoral support to people facing death and to their relatives after death. In particular, my previous professional role included putting together a pro forma list of assets and liabilities for completion by the client to help me advise them. How could I develop this idea?

Your Last Gift

It occurred to me that, if someone thought about the subject at all, they might well just think:

a) I must make a will.

b) I must outline the funeral arrangements and perhaps pay in advance.

As to a), over 50% of all UK adults haven’t made a will and will doubtless be astonished to see the impact of the ‘intestacy rules’ (set out on pages 24-25 of the book) which lay down how property is distributed when you die intestate, which means dying without having made a will.

As for b), people often haven’t given much attention to their funeral arrangements, until perhaps death is looking fairly certain. Moreover, in my experience as an ordained minister, when putting the funeral together, one of the main questions the family ask is: ‘What would they have wanted?’

The two certainties

Of course, the subject is so much broader than that. None of us likes to think about our death, but, as Benjamin Franklin famously said, death is one of the ‘two certainties in life’ (the other being taxes). So, if, when alive, we spend serious time and energy thinking about our friends and families, work, possessions, holidays and the like, it surely makes sense to give careful thought as to what happens to those we leave behind. Our death affects the overall pattern of our lives.

This book tries to keep the subject within reasonable bounds. And it’s intended to encourage not morbidity, but rather realism. I hope that Your Last Gift can be seen as part of living life to the full.

‘How would you like to die?’

‘At the end of a sentence.’

(Sir Peter Ustinov, English actor, interviewer, film-maker and writer, 1921-2004)

Setting the scene

This is a true story from my family which illustrates how tax planning can work in conjunction with advance asset planning to produce harmonious distribution of family property after a death.

The broad inheritance tax rule for lifetime giving is that a gift to one or more individuals made at least seven years before death has no inheritance tax implications, so long as the donor enjoys (or ‘reserves’) no benefit from the gift (see page 60 of the book). If full market value (in terms of an annual ‘rent’) is paid for the enjoyment, there’s no benefit reserved.

In 1998, my late mother called a family meeting for my three sisters and me. She had divided all her personal possessions into various lists according to category, eg furniture, ornaments, lamps, pictures, jewelry and so on. We four ‘children’ drew lots to decide who would start, first by selecting a category and then to determine the order of choice, both of which moved round the table. The process continued, with not a little fun and games. A careful list was made of the selection, with approximate values added and, in the end, equality of overall values was obtained through a clause in the will.

Professional valuers were instructed to put a market value on each item (in fact, two firms of valuers, one acting for the donor, the other for the donee) and also to agree the appropriate annual ‘rent’. Our solicitors drew up four deeds of gift, including provision for the annual payment of rent, which were duly signed. Mum continued to enjoy the property until the day she died, in 2010 (at least seven years after the gift). Mum paid each of us an annual rent, on which we paid income tax.

Everyone was happy – even HMRC, as while it may have missed out on the extra inheritance tax, it did get some additional income tax each year.